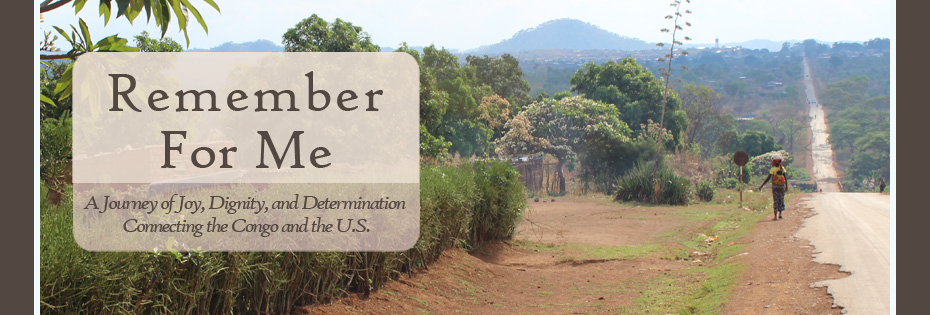

You may have

noticed a recent update to the working title of my memoir. As this memoir has

progressed and the story has unfolded, “Remember for Me” has emerged as the

title that best fits this story. Throughout the writing and editing process, I constantly

find myself thinking back to the words my mom spoke to me on a phone call from

the Congo in March 2012.

“As I am starting to forget and may not always remember

what I say or tell you, I want you to remember for me. Write it down so that

you will remember and remind me.”

With this request, my mom was asking me to remember for her in a literal sense. In the past few years her health has become more of a concern. And a recent stroke has sometimes made it difficult for her to remember details of her past.

With this request, my mom was asking me to remember for her in a literal sense. In the past few years her health has become more of a concern. And a recent stroke has sometimes made it difficult for her to remember details of her past.

But in this request, she was also asking me to remember

figuratively. To remember not just for her, but also for my grandmother, for

all of the people I grew up with, for our small village community, for my

nieces and nephews, and to remember a way of life that is connected to the

dreams of our ancestors.

Faced with our own mortality, we begin to ask ourselves: how

will we be remembered? What is worth remembering? As I write this story, I

realize that the true purpose of this story is to remember our mothers. We

remember the women they were, the women they became and honor the women, we as

their daughters, have become today—our lives intertwined, can never be completely

separated.

By remembering where we come from, we are remembering who we

are.

Remember for Me!