Even the most intimate of stories is not told in a vacuum. Storytelling by its very nature is born of collaboration—a connection between the storyteller and the audience. As the storyteller, I feel very fortunate to have a group of committed friends who have shown interest in my story and have encouraged me to share this story with a wider audience. To me, my story is just an ordinary story and

for a very long time, I did not see why anyone would be interested in reading

about it. But the more I shared the rough drafts of my life’s journey with my colleagues, the more they encouraged me to pursue a formal path of literary publication. And I am glad they were very persistent and convinced me to pursue this path.

The process of working on this memoir has been a journey of self-discovery. And one of the best decisions that I made as I decided to embark on this path was to enlist the help of my colleague Elysia Kotke. With her expertise as an editor and writer, Elysia has been able to go through and make sense of my mountains of story drafts and information about my life experiences, and she has provided the guidance for me to tell my story in a more powerful way.

It is my hope that throughout the course of 2013 you will get to meet some of my colleagues who have been very supportive with this project. And today, I would like to introduce you to one of them: Elysia Kotke. I will let her tell you about herself. Elysia, the stage is now yours…

I can remember clearly the day that I met Chingwell. As an introverted writer born and raised in the Midwest, I’m more comfortable behind the scenes; I often feel shy meeting people for the first time, but Chingwell’s genuine warmth and gentle spirit put me at ease. When I listened to her talk about her work in the DR Congo, her passion inspired me to believe again that maybe I too could make a difference in the world.

Now, having worked with Chingwell for the past three years, I feel that we have formed a unique bond. Although, we have grown up in different cultures and lived different lives, we seem to intuitively understand one another. And we are united by a mutual desire to uncover the commonalities of our experiences.

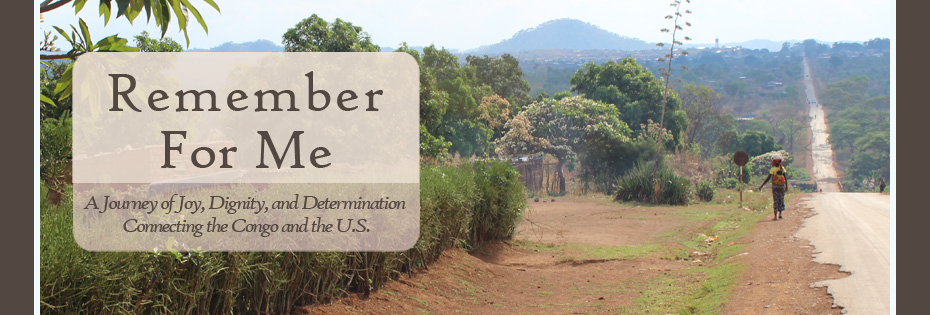

When Chingwell approached me with the idea of Remember for Me, I was thrilled by the possibility. But the reality of the project has surpassed my expectations. Through written drafts and interviews, Chingwell has shared with me the raw material of her story—her memories and experiences. And with careful hands I have worked to gently shape these stories while always striving to preserve the natural beauty of her voice and the powerful authenticity of her memories.

In this way, I have been blessed with the opportunity to stand quietly over her shoulder, to witness and connect with her stories—and to discover the universal truths and experiences that unite our different lives and cultures. I have laughed and cried; I have learned so much.

Last week, I attended a local school with Chingwell as she read a few excerpts from the chapters we have worked on together so far. As Chingwell read a passage from Remember for Me in which she visits her favorite river stream at five years old, the 12th grade students leaned forward to catch her soft words. When she finished, the class was silent. Then, one by one the students began to share their thoughts. One girl said “I remembered what it felt like to be five again. I felt like I was with you, but I also felt like I was myself as a child. As you were running through the jungle, I was running through my woods.”

Chingwell’s story is powerful and universal. It is the story of children everywhere—their curiosity and joy, but it is also the story of a very specific place and time, the story of what it was like to grow up as a child in a village in the DR Congo at that time. My role in this project is to edit and guide this story, to represent the audience, and to continue supporting the tender bridge of words which will one day allow many other readers to cross over and meet Chingwell as well.

The process of working on this memoir has been a journey of self-discovery. And one of the best decisions that I made as I decided to embark on this path was to enlist the help of my colleague Elysia Kotke. With her expertise as an editor and writer, Elysia has been able to go through and make sense of my mountains of story drafts and information about my life experiences, and she has provided the guidance for me to tell my story in a more powerful way.

It is my hope that throughout the course of 2013 you will get to meet some of my colleagues who have been very supportive with this project. And today, I would like to introduce you to one of them: Elysia Kotke. I will let her tell you about herself. Elysia, the stage is now yours…

“Words form a tender bridge extending across distances of time and space to create a place where author and audience can connect.” - Anonymous

I can remember clearly the day that I met Chingwell. As an introverted writer born and raised in the Midwest, I’m more comfortable behind the scenes; I often feel shy meeting people for the first time, but Chingwell’s genuine warmth and gentle spirit put me at ease. When I listened to her talk about her work in the DR Congo, her passion inspired me to believe again that maybe I too could make a difference in the world.

Now, having worked with Chingwell for the past three years, I feel that we have formed a unique bond. Although, we have grown up in different cultures and lived different lives, we seem to intuitively understand one another. And we are united by a mutual desire to uncover the commonalities of our experiences.

When Chingwell approached me with the idea of Remember for Me, I was thrilled by the possibility. But the reality of the project has surpassed my expectations. Through written drafts and interviews, Chingwell has shared with me the raw material of her story—her memories and experiences. And with careful hands I have worked to gently shape these stories while always striving to preserve the natural beauty of her voice and the powerful authenticity of her memories.

In this way, I have been blessed with the opportunity to stand quietly over her shoulder, to witness and connect with her stories—and to discover the universal truths and experiences that unite our different lives and cultures. I have laughed and cried; I have learned so much.

Last week, I attended a local school with Chingwell as she read a few excerpts from the chapters we have worked on together so far. As Chingwell read a passage from Remember for Me in which she visits her favorite river stream at five years old, the 12th grade students leaned forward to catch her soft words. When she finished, the class was silent. Then, one by one the students began to share their thoughts. One girl said “I remembered what it felt like to be five again. I felt like I was with you, but I also felt like I was myself as a child. As you were running through the jungle, I was running through my woods.”

Chingwell’s story is powerful and universal. It is the story of children everywhere—their curiosity and joy, but it is also the story of a very specific place and time, the story of what it was like to grow up as a child in a village in the DR Congo at that time. My role in this project is to edit and guide this story, to represent the audience, and to continue supporting the tender bridge of words which will one day allow many other readers to cross over and meet Chingwell as well.